|

IT'S TRAD, GRANDAD

The article appears by Kind permission of

Jazz Rag

ANDREW LIDDLE looks back

Trad

Mad, by Brian Matthew, is a book I bought and devoured in its year

of publication, 1961, which has been on my shelves unread for years.

It makes fascinating reading about pop music at its precise moment

in time. In these changed days I have returned to it to review it

retrospectively with the clarity of hindsight and the certain

knowledge of where it was perceptive and where it was, alas, badly

wrong. Trad

Mad, by Brian Matthew, is a book I bought and devoured in its year

of publication, 1961, which has been on my shelves unread for years.

It makes fascinating reading about pop music at its precise moment

in time. In these changed days I have returned to it to review it

retrospectively with the clarity of hindsight and the certain

knowledge of where it was perceptive and where it was, alas, badly

wrong.

Culturally, it represents where my love of jazz first began and

where it is rooted even if I have subsequently travelled much in its

realms of gold, and many goodly styles and syncopations heard. It is

difficult to convince people who were not around in the 1950s and

early ’60s how popular such music was among teenagers. There was an

immensely pretty girl who sat in front of me in class at school who

gave me a flash of Humph’s smiling teeth and gleaming trumpet every

time she lifted the lid of her desk. Yes, Trad was pop although pop

was not Trad, but a mixture of it, rock’n’roll and Tin Pan Alley.

‘Freight train … freight train … going so fast …’

I can hear it now, in memory, so many years later. Freight Train was

the song of the summer of 1957, never off the wireless, heard coming

out of doors and windows, filtering through the neighbours’ walls or

being sung by passing strangers. For me, 1957 is the one summer I

remember, musically, in almost every detail, like a film shot in the

sort of ‘glorious technicolour’ that was beginning to goggle the

eyes of cinema-goers. And Chas McDevitt’s big hit, a Skiffle

sensation, provides the sound track. I loved that record, its

poignant lyrics and infectious rhythms, but it was Lonnie Donegan’s

Rock Island Line, around Christmas 1955, that had first awoken my

interest and I’d wager that of the girl who sat in front of me and a

generation of Trad Jazz lovers, who make up the grey audience in our

jazz clubs.

It was a natural process, it seemed, to go from Skiffle to Trad.

Matthew writes about Trad as an immense popular musical phenomenon,

an established fact which is here to stay. Even allowing he is

writing uncritically for very largely a teenage audience, his book,

for all its naive misreading of the future, actually is a hugely

important historical document. It offers a fascinating insight into

the cultural zeitgeist of the period betwixt rock’n’roll and

Beat(les’) music briefly occupied by Trad Jazz and how much the BBC

and, therefore, the country was still under the prescriptive and

proscriptive moral influence of Lord Reith, former Director General

of the BBC.

‘Nowadays the pendulum has swung away from Rock,’ he writes, by

which he means rock’n’roll. He says, cleverly, that lots of people

thought this was the time for calypso to take over but, no, they

were very much mistaken. He, in the music business, with his finger

on the pulse, is happy to put them straight.. ‘It looks as though

the sixties may well come to be labelled the ten years of Trad,’ is

his confident opening assertion. As far as he is concerned, this is

the music synonymous with ‘present day entertainment’. He was

monumentally wrong on two counts but could, perhaps, no more have

predicted the arrival of twanging foursomes than we might have

spotted Covid on the horizon. The popularity of rock’n’roll (‘the

simplest thud and crash form of beat music’) had, indeed, waned, but

it would never go away for the next sixty years. Alas, as pop music,

Trad did. In fact its mainstream course barely had more than

eighteenth months to run. Matthew was writing at both its zenith and

apogee.

For page after page Matthew writes with utter conviction about

Trad’s never-ending appeal, linking its enduring success to the fact

that Jazz had already been around for at least fifty years. He was,

intriguingly, both very wrong and totally right. The music would

survive for the minority, as our Trad Jazz clubs attest, but not for

the many who tuned into his programmes.

It’s a slim book, 125 pages, with only eight chapters, written in a

light conversational tone. I remember the author best as a radio

disc jockey with a warm sunny voice who hosted Saturday Club,

compulsory listening for me before I set off early to the football

in the afternoon. A sunny disposition is confirmed in his writing,

even shining though the occasional clouds of morality gathering

overhead. Though he was no different from other record-spinners in

that he moved on and embraced other styles throughout a long career,

it seems clear that he did have a deeply sincere love of Jazz and

was very knowledgeable about the contemporary scene, less so about

the music’s history.

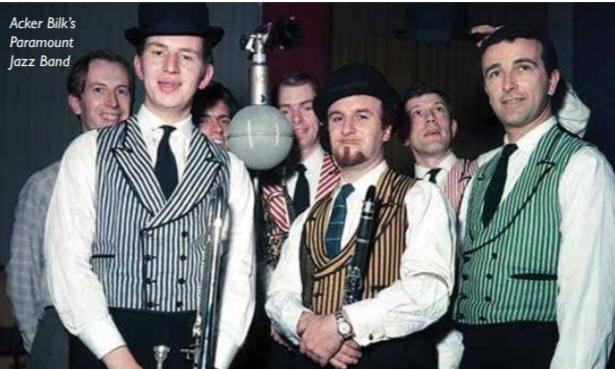

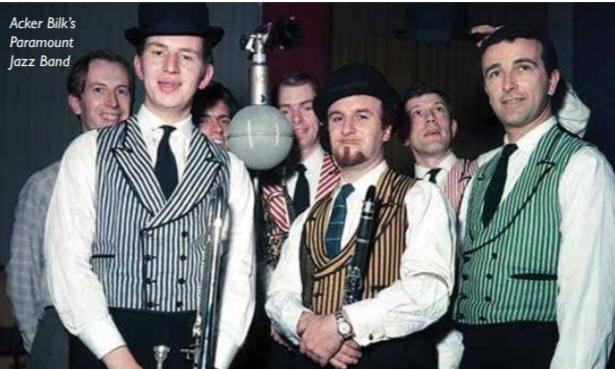

Usually

when he tips someone for success, he is about right, notwithstanding

the music’s decline in popularity. The majority of the book is given

over to three bands that had just topped the BBC’s 1961 popularity

poll, Kenny Ball’s, Acker Bilk’s and the Temperance Seven. The last

named sneak into the pantheon by some sleight of hand: they are not

Trad, but Trad enthusiasts like them. In later chapters, he speaks

of ‘the big six’, to which are admitted Chris Barber, Terry

Lightfoot and Alex Welsh. Two more tipped for the big time are Bob

Wallis’s Storyville Jazzmen and Dick Charlesworth’s City Gents. Usually

when he tips someone for success, he is about right, notwithstanding

the music’s decline in popularity. The majority of the book is given

over to three bands that had just topped the BBC’s 1961 popularity

poll, Kenny Ball’s, Acker Bilk’s and the Temperance Seven. The last

named sneak into the pantheon by some sleight of hand: they are not

Trad, but Trad enthusiasts like them. In later chapters, he speaks

of ‘the big six’, to which are admitted Chris Barber, Terry

Lightfoot and Alex Welsh. Two more tipped for the big time are Bob

Wallis’s Storyville Jazzmen and Dick Charlesworth’s City Gents.

Ken Colyer’s name crops up occasionally but slightly dismissively -

as ‘that stalwart of New Orleans purists’. Late in the day, he adds:

‘There can scarcely be a jazz man of note whose career has not been

influenced at some point by Colyer’ – yet in total the Guv’nor is

afforded no more than five lines when Jackie Lynn, for example, a

glamorous and largely forgotten vocalist with Dick Charlesworth,

gets three pages, about the same coverage as Ottilie Patterson.

Did jazzmen at the time really refer to each other and everyone else

as ‘Dad’? Many do in this book including Acker, ‘a

gentleman-farmer’, who seems incapable of addressing anyone

otherwise. Acker receives high praise for rehearsing thoroughly and

being uncompromisingly self-critical. We learn how meticulous he is

in keeping detailed records of the band’s repertoire ‘annotated with

such necessary information as the duration and tempo of each

number’. On the stand, however, it is Colin Smith, the trumpeter

with ‘a phenomenal memory’, who calls the key and the order of

solos.

Writing in a period with a different moral compass from that of the

present, Matthew feels an obligation to mention Acker’s court

martial and dishonourable discharge from the forces and brief

imprisonment. It seems that this blot is somehow effaced, however,

by his subsequent appearance at a Royal Variety enough to be

presented to the Queen Mother, we can have no fear about his

standing and, indeed, his band had just been voted by New Musical

Express readers as ‘top trad group of 1961, with a clear lead of

2,000 points over its nearest rival.’ Royal patronage only just

trumps mass popularity in establishing bona fides.

That nearest rival happens to be Kenny Ball, and his radio

appearance on Sunday morning’s Easy Beat was apparently the subject

of much discussion in Reith-redolent BBC corridors. It seems Jazz

was fine for Saturdays but, well, Sundays were different. Matthew is

happy to expatiate on his own role in persuading the assistant head

of the Light Programme, Jim Davidson, to give it a try. Initially

‘with appropriate caution’ Kenny Ball was booked for a four-week

trial. After making a ‘colossal impact’, he had his first big hit

with Samantha and was kept on for the next seven months. ‘It’s

ridiculous, Dad,’ was Kenny’s verdict, blown away by not being able

to find a jazz club big enough to accommodate his fans.

There is almost the sense that all this might get out of hand and a

word of caution is interjected. Such was the popularity of the music

that the very label ‘Trad’ in some quarters was ‘sufficient in

itself to mean success for many bands playing very bad jazz …

offensive to the ear’. The message seems clear: it’s much safer, all

round, to stay with radio Jazz and keep buying the records.

The Temperance Seven have a whole chapter to themselves and in spite

of being treated for the most part as a novelty act, creating their

own eccentric ‘myth’ and ‘odyssey’ (presumably what today would be

called ‘image’), at heart they are sincere musicians ‘who will

remain a top attraction for a very long time’. At least that was

true in part.

Chris Barber is lumped in a chapter with ‘three of the best’,

although rated by many Jazz fans as ‘not only the most popular but

by far the best band in Britain.’ Chris is not apparently the sort

of chap to call anyone ‘Dad’ and, it slightly amuses the author,

that he loathes the very word ‘Trad’, feeling it is restricting and

giving a false impression. Anyone who has ever met Chris will not be

surprised to hear his slightly pedantic alternative: ‘creative jazz

… in the traditional idiom’. Matthew goes on perceptively to

describe Chris’s entrepreneurial instincts, his ‘brilliance at

mathematics’ and his ‘built-in slide-rule’. One suspects that this

might be euphemism for saying Chris knows his own value and drives a

hard bargain - slightly surprising from a man so ‘quiet and

unassuming’.

There is some suggestion that Matthew does not entirely revere this

man, for all Chris’s acknowledged devotion to Jazz. He comes across,

in the modern parlance, as something of a control freak and

tight-fisted to boot, adding up restaurant bills in advance and

correcting mistakes. Greed rears its ugly head, in fact. ‘As far as

eating goes, Chris takes the cake, and not only that, but as many

other courses as any restaurant is capable of serving. At meal times

he really comes into his own, and it is then that his alcoholic

indulgence becomes apparent.’ Apparently Chris has a naughty taste

for white wine, too, and sometimes, amusingly, ‘gets to the giggly

stage.’ Who would have thought it!

In a book full of incidental comments, many of them trivial and

transitory, one of the most far-sighted is reserved for trombonist,

Roy Williams, about 24 at the time and working with Mike Peters: ‘ I

firmly believe we are going to hear a great deal of Roy Williams …

[and] … it wouldn’t really surprise me if he eventually … became a

modernist.’ Banjoist Hugh Rainey is perceptively singled out for his

brilliance and great promise.

Finally, Matthew touches on televised Jazz and his involvement with

the short-lived and well-named Trad Fad, preening himself for having

been the original compčre for the only television programme to

feature nothing but Trad. The set, designed by Cephas Howerd, of the

Temperance Seven, was ‘clean, modern and spacious, as far removed as

possible from many a jazz cellar’. To maintain visual interest

professional dancers were employed. The audience was by invitation

only and there were ‘no beatniks and no weirdies.’ Jeans were

impermissible; girls had to wear skirts. It does get even more

patronising: ‘the great unwashed, with their bizarre clothes and

offbeat habits,’ to be found in jazz clubs, were excluded.

The producer, Johnny Stewert, declared himself to be on a mission

‘to prove to detractors that it is a most entertaining form of

music, which does not have to be presented in dirt and discomfort’.

He is quoted as saying: ‘I have built a clean, bright set and I want

it filled with clean bright people who enjoy jazz’.

Trad Fad was not long lived.

Reading the book again after so many years and now in possession of

some critical judgement, it becomes crystal clear that the Trad

Boom, so called, was merely a manifestation of Tin Pan Alley, rather

than a radical alternative to it. In this respect, we ought not to

be surprised it came and went like a shooting star. Like many and

indeed most manufactured pop cults it lasted only until the next

craze came along.

Its demise had nothing to do with the intrinsic merits of its music.

It had run its course and was eclipsed in the popular consciousness

by something new, which I forebear to mention. The real traditional

jazz had been played in rhythm clubs from the late 1940s onwards and

is still alive in our jazz clubs. So good is it that it has survived

without significant changes in style or substance.

Trad fads for Trad-mad Trad dads was commercially inspired and

embraced by two types of people: those who are always into the

latest thing and quickly tire; and those who developed a genuine

love for it and stuck with it. The real stout oaks of their

generation, not blown about by every modish breeze, still listen to

it and those still able attend it in their clubs. This second group

were never ‘Trad mad’ but simply intoxicated, body and soul, by

jazz’s heady brilliance. Having once had a taste of it, they could

never give it up.

Let’s hope they can return soon, post-Covid.

|

Usually

when he tips someone for success, he is about right, notwithstanding

the music’s decline in popularity. The majority of the book is given

over to three bands that had just topped the BBC’s 1961 popularity

poll, Kenny Ball’s, Acker Bilk’s and the Temperance Seven. The last

named sneak into the pantheon by some sleight of hand: they are not

Trad, but Trad enthusiasts like them. In later chapters, he speaks

of ‘the big six’, to which are admitted Chris Barber, Terry

Lightfoot and Alex Welsh. Two more tipped for the big time are Bob

Wallis’s Storyville Jazzmen and Dick Charlesworth’s City Gents.

Usually

when he tips someone for success, he is about right, notwithstanding

the music’s decline in popularity. The majority of the book is given

over to three bands that had just topped the BBC’s 1961 popularity

poll, Kenny Ball’s, Acker Bilk’s and the Temperance Seven. The last

named sneak into the pantheon by some sleight of hand: they are not

Trad, but Trad enthusiasts like them. In later chapters, he speaks

of ‘the big six’, to which are admitted Chris Barber, Terry

Lightfoot and Alex Welsh. Two more tipped for the big time are Bob

Wallis’s Storyville Jazzmen and Dick Charlesworth’s City Gents.