|

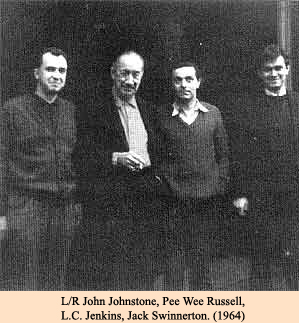

The Manchester Sports Guild (M.S.G.) Jack Swinnerton died peacefully on 30th June 2008 Part 2: ‘Opening Night’ by Jack B. Swinnerton The opening night at the new MSG Sports and Social Centre on Long Millgate, almost adjacent to Manchester Cathedral, in the Spring of 1961 was a memorable occasion. The then Committee members of ‘Buck’ Taylor, Harry Henderson, John Orr, and General Secretary ‘Jenks’ were joined by Leslie Lever MR He had been invited as special guest for the evening to dedicate and ‘screw-in’ the wall plaque in celebration of this first members’ night. Jenks, despite his preferred image of slippers, sweater and pint of Guinness in his presentation tankard, would quite enjoy the very occasional lounge suit and conservative evening (conservative with a small 'c' Jenks, if you’re snarling out there somewhere), and this was one of them. Dedicated people, most of whom were volunteer members, had put many weeks of work into the place by then. Whilst present on the opening night, I was in no way involved at that time but well remember the odour of drying paint and varnish in the air. The jazz cellar itself had been decorated, and some will recall the red tinted paint on the floor which refused to dry. Despite a non-dancer, the stuff would adhere to shoes nightly and for months -goodness knows how they emerged!

Those of us with day-time occupations in the immediate vicinity benefited from the lounge bar open at lunchtime. (I was only yards away, obviously a factor in enabling eventual closer involvement.) It was most enjoyable to stroll in for a couple of pints, into an uncrowded midday lounge, even play my own records or reel-to-reel tapes and generally chat with fellow sympathisers. Forgetting for the moment the fine jazz performances on the horizon, it would appear that for us locals the atmosphere for which the MSG lounge is well remembered is its fine feeling of togetherness. People with this minority interest would gather together in a thoroughly welcoming atmosphere to discuss the latest jazz records and play their favourites, with no disapproving glances. Keith Morey, who collected the jazz cellar door admission charge, had become a close friend over the years, and my occasional standing-in for him was the beginning of my closer practical involvement with the jazz. Keith and I were both very keen record collectors (and silent and early sound film enthusiasts, too - how often one seems to spot these two interests in common) and would occasionally rival each other in prompt purchase of re-issued gems. Some will recall Keith as the drummer with The Southside Stompers, based at the Black Lion in Salford. He rapidly departed when the ‘modern’ element started to come through. Under the leadership of Roy Bower on trumpet, it eventually became quite a contemporary group as one can detect through the evolving names of Southside Stompers via Southside Jazzmen into the Southside Sextet, and thence into a ballroom residency at the MSG as the Roy Bower Sextet (reedman Harold Salisbury is still active in the Preston area, and I think Roy moved somewhere down South. Is he still active?). Keith was far from ignorant of the later developments of the music, but had suddenly recoiled from such influences, at least at that time, for a strict appreciation of New Orleans-style. Even such as Bix or Luis Russell had become dangerous deviants in his eyes, and it is easy to recall the sardonic glance that the unwary would encounter in casual discussion. It was a regrettable day when such a character emigrated to New Zealand - is he there still, I sometimes wonder? -and the inheritance of many of his treasured 78s before departure was much appreciated. They are all still played and intact, Keith.

Over the months, Jenks and I had become well acquainted, and late evening discussions about the potential of the centre and its scope on the jazz scene were a recurring topic. Upon asking me to assume control of MSG jazz bookings, he had presumably assessed my enthusiasm and discovered that, by nature and career, I could claim to be a methodical and responsible person. Then the production manager of one of Manchester’s largest advertising agencies, schedules and tight deadlines were an integral part of life, and what might have appeared as complications in other fields were simply daily routine. The work was on a voluntary basis but, as my leisure hours were now largely spent there, it was immediately seen as an interesting and stimulating challenge. At my time of taking on the role as jazz organiser, it will be remembered that we had just experienced the ‘Trad-boom’ which peaked c.1960/61, and audiences would now be expected to decline dramatically. As a strict members club, and a jazz crowd not remarkably fond of the fancy dress years, it would nevertheless reverberate. Our dedicated enthusiasts were going nowhere else and, indeed, the recently disillusioned would probably return to hear the genuine jazz groups still playing. Our principle night in terms of attendance and consequently the financial mainstay of those early years was the Friday night local band session, brought across from The Sportsman as recalled last month. In the very beginning, this Friday audience was dominated by young, very pleasant, pacific people with exaggerated dress sense, ‘Ban the Bomb’ badges, and a characteristic style of dance. They would greet one another with a circular wave of outstretched palms and usually spoke softly. Spike Milligan-derived voices seemed apparent, but were acceptable to a Tony Hancock devotee such as myself! It soon became apparent that the jazz cellar bandstand located at the farthest end of the cellar from the bar was not positioned well. On reasonably full evenings, one would enter to witness a sound-muffling mass of dancers/listeners in the centre, effectively hindering participation from the bar. This was still the heyday of the waiter, manoeuvring through crowds with tray aloft, and the ability to supply a drink was what made it viable. A move to the centre, by the wall, was an improved location, providing a considerably enhanced listening area with a semi-circle of tables and chairs. (Those who recall a third enlarged stand are right - a somewhat larger area in the same spot was required for Earl Hines and the grand piano - but that’s looking ahead.) Whilst readers of this series will naturally be more interested to hear of the legendary names as yet on the horizon, it is important to lead up to the events. Incidentally, having been only too well aware for years of the benefit that the MSG heyday was about to bring to the nation’s jazz scene (this is not a boast - no one could foresee) it had not occurred until more recently that there was some reciprocal advantage. Earl Hines regained the spotlight back home and Ruby Braff was portrayed sympathetically by the late Steve Race in ‘Jazz News; May, 1962, as ‘The Jazzman Nobody Wants' That seems ludicrous today - but perhaps he was right then. About all I had was those wonderful Vanguard sessions. It was enough to convince for the eventual tour. (Another irrelevance: I’ve just noticed in ‘Just Jazz’ No. 1, Quiz Time, Item 4. What did MSG mean? -let’s hope it is coming across.)

Another aspect of the MSG was the registered theatrical agency known as Millgate Entertainments. All engagements were booked through this agency of which John Pye and I were partners (although we lost contact for over 25 years, John and Eunice Pye and my wife Jennifer and I now enjoy regular chats again). At that time, my advertising career was in full swing, and John was a local school headmaster. Neither of us received, nor needed, income from this work, the same for my role as MSG jazz organiser. Any capital from this venture was ploughed straight back into sport and music. One controversial aspect of the agency was the ‘barring clause' I no longer possess copies of our contracts, but the clause was something like a 15 mile radius from the centre for a few weeks either side of the engagement. In the days of fame, we would usually book a band at their going rate for a Saturday evening performance, and were not inclined to negotiate as hard as some for reductions. Having secured a reasonable and sometimes generous salary (the signed contract binding both parties, of course), a travelling band would naturally like to obtain an adjacent date nearby. What is probably not widely known, except amongst bandleaders, is that we were able to help provide bands travelling some distance with carefully spread bookings. Carlisle Jazz Club operated their venue on a Sunday and, as a small but ambitious set-up, were extremely keen to accept our previous night’s band at the very competitive rates we could then obtain. Similarly, the renowned Dancing Slipper at Nottingham were frequently co-operative in the chain, and there were others, too. What would happen should these adjacent gigs be somewhat closer and in other hands? Let us say Stockport and Bolton as examples. A short-sighted band leader (most of them weren’t, and thoroughly agreed with us) could possibly think that this would be lucrative in terms of travelling and accommodation, and the well paid Saturday session enable them to demand less money. And, in theory, it would work very well for them, but only for the first time. The other venues, paying less on the strength of our Saturday, would be able to charge less at the door and we, the event instigators, would be the ones to suffer first. Excessive exposure in a small catchment area breeds the disinterest of over-familiarity and tends to expose such not uncommon failings, for example, as a somewhat limited repertoire. Next time round, the turnout would start to drop and the fees inevitably go the same way. The band, the audience, and the promoters all become victims.

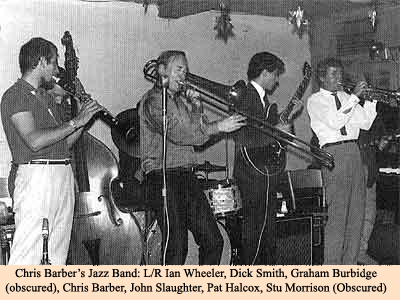

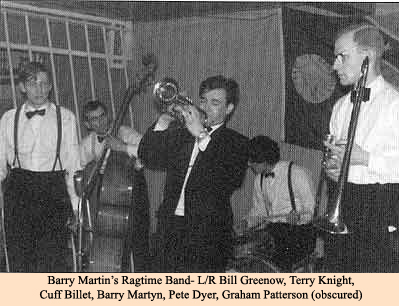

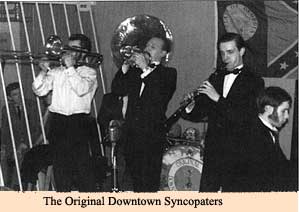

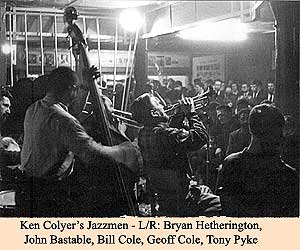

This was a breakthrough which, strangely enough, really began with the quality end of the market -some of the people we particularly wanted to feature. We were quite quickly able to absorb Bruce Turner’s Jump Band and Sandy Brown/Al Fairweather into the schedules. To experiment was most interesting, and to be able to announce such varied nights with Mike Daniels’ Big Band, Humphrey Lyttelton, Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen, or the just reemerged Freddy Randall band was stimulating. I believe that it is fair to claim that no other venue made such a determined effort to make a speciality of seeking out so many of the lesser known bands from all over the country. Such as Barry Martyn, Steve Lane, Keith Smith, or the Original Downtown Syncopators had southern reputations, very little known up north. They would soon become welcome and frequent visitors. Leading bands from the provinces such as the Second City Jazzmen, the Merseysippi Jazz Band or Mick Shore’s various groups, too ,were actively encouraged in practical ways - even featuring some in support of distinguished visitors on occasion. There was by now insufficient audience to continue to feature such as the Dutch Swing College Band or Chris Barber and Ottilie Patterson at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, but our rare ‘House Full’ notices would have to be placed in the cellar. And really, the surroundings were more stimulating than a concert hall. There were sufficient enthusiasts to support our policy at this time, but they were a reduced segment from what had recently been the numerous clubs around. As the climate shifted to other “musical” sounds (the dreaded four had now moved from jazz band interval support to main feature at Liverpool’s Cavern, for example) so the disenchanted throughout the area applied to join our thriving membership.

He was pleased that the jazz reputation of the MSG was now nationally respected and wished to thank the enthusiasts with a 10th anniversary we would never forget. A constant late night eavesdropper, he had become very aware of our awe of the American originators and encouraged me to move in that direction. I must confess considerable doubt that we would accomplish something quite so ambitious. Jenks, always remember, generously gave us the opportunity and ideal premises to indulge ourselves, but was not aware then of Musicians’ Union restrictions or other potential problems. Such as the Bechet/Lyttelton appearance some years previously, for example. Nevertheless, a wonderful invitation to a young enthusiast such as myself, but - would it ever happen? Not till part three. Part 3... Please Visit my HOME PAGE

|

The ground floor consisted of a lounge

bar with plain tables and stack chairs, fruit machines and pin tables. It would

not be considered a comfortable resting place today but, in those times, it was

a remarkable oasis and rest for people of similar interests. The first floor was

what Jenks, no doubt recalling his youthful days between the wars, would

identify as ‘the ballroom'. Initially a barren area, with the

later addition of a third bar, it came into its own. Private functions, big band

nights and, of course, Manchester’s Club 43 for a short time. (Whilst not an

enthusiast myself, the folk nights were a separately run series organised by

Frank Duffy and much celebrated on the folk scene.) The second, and top, floor

was mainly occupied with a large judo mat and changing/shower room. Jenks’

living quarters and the committee offices were housed beyond the mat. The memory

of working, answering ‘phones and drawing up schedules through pounding feet,

crashing torsos, and occasional waves of sweat is still vivid today.

The ground floor consisted of a lounge

bar with plain tables and stack chairs, fruit machines and pin tables. It would

not be considered a comfortable resting place today but, in those times, it was

a remarkable oasis and rest for people of similar interests. The first floor was

what Jenks, no doubt recalling his youthful days between the wars, would

identify as ‘the ballroom'. Initially a barren area, with the

later addition of a third bar, it came into its own. Private functions, big band

nights and, of course, Manchester’s Club 43 for a short time. (Whilst not an

enthusiast myself, the folk nights were a separately run series organised by

Frank Duffy and much celebrated on the folk scene.) The second, and top, floor

was mainly occupied with a large judo mat and changing/shower room. Jenks’

living quarters and the committee offices were housed beyond the mat. The memory

of working, answering ‘phones and drawing up schedules through pounding feet,

crashing torsos, and occasional waves of sweat is still vivid today. MSG jazz organiser John Orr had

suffered a drastic deterioration in health during the summer of 1961 and, one

autumn evening, Jenks announced to a saddened audience in the cellar that he had

succumbed to cancer. That left the centre without anyone to control the jazz

bookings.

MSG jazz organiser John Orr had

suffered a drastic deterioration in health during the summer of 1961 and, one

autumn evening, Jenks announced to a saddened audience in the cellar that he had

succumbed to cancer. That left the centre without anyone to control the jazz

bookings. It was felt necessary by Jenks and

myself to have a formal chat with the local musicians about what we saw as the

future of jazz at the club. Since the decline of The Bodega, it had become the

biggest jazz centre in Manchester and it seemed sensible and progressive to

widen and present an out-of-town band most weekends. Widening appreciation was

perceived to be the way to maintain attendance levels now that the young were

moving to other forms of music. Naturally, not all musicians were immediately

pleased, despite assurances that midweek sessions would increase (and they

did, as contemporary programmes illustrate).

It was felt necessary by Jenks and

myself to have a formal chat with the local musicians about what we saw as the

future of jazz at the club. Since the decline of The Bodega, it had become the

biggest jazz centre in Manchester and it seemed sensible and progressive to

widen and present an out-of-town band most weekends. Widening appreciation was

perceived to be the way to maintain attendance levels now that the young were

moving to other forms of music. Naturally, not all musicians were immediately

pleased, despite assurances that midweek sessions would increase (and they

did, as contemporary programmes illustrate). Alex Welsh, as some will remember,

appeared with us for the first time on the relatively ‘dead’ Thursday night.

It was a memorable evening. I had been a Welsh enthusiast ever since hearing

those 1954 Royal Festival Hall recordings, and had been impatiently awaiting the

chance to book them. Can you imagine why I would book a band of their magnitude

to make its first appearance with us on a Thursday? It was the first gap in

Paddy McKiernan’s ‘Bodega/Mr. Smith’s’ bookings and, consequently, his

barring clause had lapsed. With full calculation, I leaped at the opportunity,

booking them for that night and subsequent Saturday dates simultaneously. I

recall going out into the street to meet Alex on that first night. Of course, I

knew him well by sight, but we’d never met and he knew nothing of our

ambitions at that stage. All the men were casually dressed and Lennie (Hastings)

turned to Alex at the rear of their van with, “Is it uniforms tonight, Alex?”

With a swift glance at our fairly stark premises in the chill night air, he

responded with, “No, I don’t think so!”

Alex Welsh, as some will remember,

appeared with us for the first time on the relatively ‘dead’ Thursday night.

It was a memorable evening. I had been a Welsh enthusiast ever since hearing

those 1954 Royal Festival Hall recordings, and had been impatiently awaiting the

chance to book them. Can you imagine why I would book a band of their magnitude

to make its first appearance with us on a Thursday? It was the first gap in

Paddy McKiernan’s ‘Bodega/Mr. Smith’s’ bookings and, consequently, his

barring clause had lapsed. With full calculation, I leaped at the opportunity,

booking them for that night and subsequent Saturday dates simultaneously. I

recall going out into the street to meet Alex on that first night. Of course, I

knew him well by sight, but we’d never met and he knew nothing of our

ambitions at that stage. All the men were casually dressed and Lennie (Hastings)

turned to Alex at the rear of their van with, “Is it uniforms tonight, Alex?”

With a swift glance at our fairly stark premises in the chill night air, he

responded with, “No, I don’t think so!” Were Jenks still alive today, I have no

doubt that he would reiterate his claim that his interest in, and knowledge of

jazz was slight. He was surrounded by enthusiasts, even fanatics, and enjoyed

the company of some of them (he might also remind you - not all of them), and

the excitement must have been infectious. He had occasionally to be

affectionately steered away from jazz discussion. Sensing that Coleman Hawkins

was about to emerge as a trombonist in a developing conversation with a politely

wide-eyed Sinclair Traill from ‘Jazz Journal a discreet cough from a John Pye

carefully veered the topic around. Yet to give all due credit - it is this very

innocence that sparked the innovations just ahead.

Were Jenks still alive today, I have no

doubt that he would reiterate his claim that his interest in, and knowledge of

jazz was slight. He was surrounded by enthusiasts, even fanatics, and enjoyed

the company of some of them (he might also remind you - not all of them), and

the excitement must have been infectious. He had occasionally to be

affectionately steered away from jazz discussion. Sensing that Coleman Hawkins

was about to emerge as a trombonist in a developing conversation with a politely

wide-eyed Sinclair Traill from ‘Jazz Journal a discreet cough from a John Pye

carefully veered the topic around. Yet to give all due credit - it is this very

innocence that sparked the innovations just ahead.