|

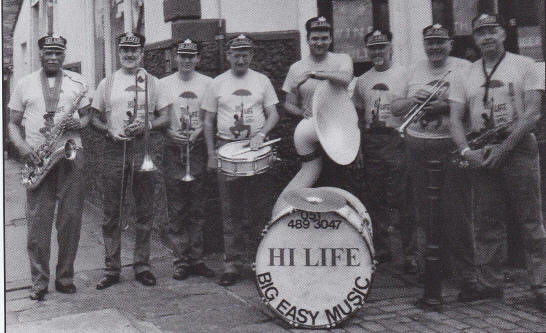

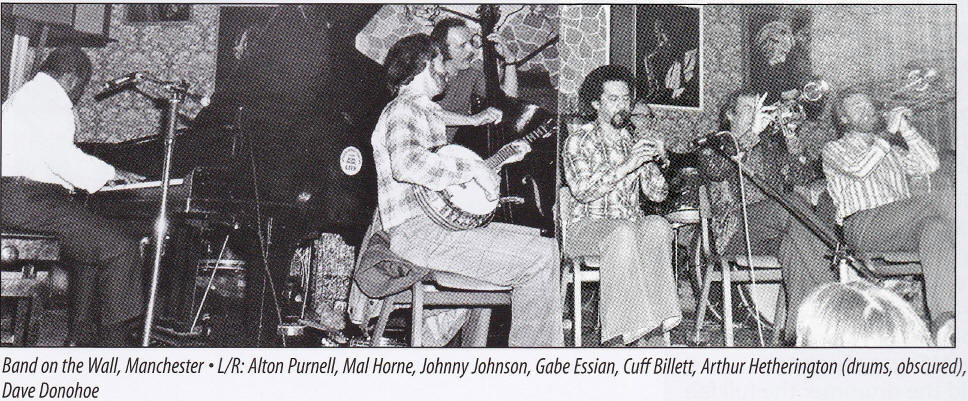

Looking after the Legends Reproduced by kind permission of Dave Donohoe and Just Jazz magazine Thanks to Tom Stagg and Richard Millward for helping me with my memory lapses, and to Teddy Fullick for proof reading. - Dave Donohoe

Over the years, every time I have related an amusing incident

involving a visiting American musician, someone inevitably says,

"You should write these things down." I usually reply that I

will, but then do nothing. During this time, Barry Martyn had moved to California. He

started a music agency named Westerburg Associates. Tom Stagg,

then still living in London, was to control the British part of

the tours.

The first time he arrived at our home, my wife and youngest

daughter Clare were the only ones at home. Clare was about seven

or eight at the time, and she gazed open mouthed at the first

black person she had ever seen. Alton sat down in an armchair

with a cup of tea, but was aware that Clare was slowly sneaking

up on him from the side. When she was within touching distance

her arm slowly reached out and she rested her hand slowly on his

head. She then began to run her fingers through his short,

crinkly hair. When he became aware of what she was doing he

simply sat back with a contented smile on his face, and let her

continue with her new-found interest. The first time he arrived at our home, my wife and youngest

daughter Clare were the only ones at home. Clare was about seven

or eight at the time, and she gazed open mouthed at the first

black person she had ever seen. Alton sat down in an armchair

with a cup of tea, but was aware that Clare was slowly sneaking

up on him from the side. When she was within touching distance

her arm slowly reached out and she rested her hand slowly on his

head. She then began to run her fingers through his short,

crinkly hair. When he became aware of what she was doing he

simply sat back with a contented smile on his face, and let her

continue with her new-found interest. The next day I drove him to Rotherham in S.W. Yorkshire to play with the Dave Brennan Band. The hotel we were booked in was also the concert venue, which was a bonus. I booked us in, gave Alton his room key and told him that I would meet him in the bar in thirty minutes. The bar was empty, but I could hear voices coming from an adjoining room so I looked in out of curiosity and was surprised to see a children's fashion show in progress, complete with catwalk that came from a curtain. Up to then my only experience of Rotherham was of playing at miners' galas with a marching band, or in working men's clubs where beer had to have a big frothy head on it. I'm a proud Northerner but I do like a flat southern beer that reaches the top of the glass. The people spoke in an old fashion biblical dialect with plenty of thees and thous. I had never encountered the posh side of town. The lady commentator was telling the audience that the event was being sponsored by someone with a name like Lady Caroline Withering-Scornforth. She then went on to say; "Next we have Guinevere in a Bo Peep dress with blue bonnet with a blue polka dot bow." Guinevere then appeared through the curtain, strutted down the catwalk, curtsied and retreated through the curtain. The commentator then announced Thurston in a navy blue sailor suit and white cravat. All the women clapped (there were no men present apart from me) the curtain was pulled aside, and out stepped Alton Purnell.  For those who never saw Alton, he wasn't very tall, about 5ft

5in or 5ft 6in and he was more black than brown with smiley,

twinkly eyes. His face had a battered Mike Tyson look, probably

from his early days as a pugilist. The applause came to a sudden

halt followed by open-mouthed amazement. What happened next is

hard to believe unless you were there. In a second, Alton

realised what he had walked into, smiled at the audience,

curtsied and strutted down the catwalk in short effeminate steps

with one hand on his hip. At the end of the catwalk he bowed

with one arm behind his back and retreated back through the

curtain. By then, the women and kids were laughing out loud and

applauded as if they'd witnessed a performance by a top

entertainer. They had! For those who never saw Alton, he wasn't very tall, about 5ft

5in or 5ft 6in and he was more black than brown with smiley,

twinkly eyes. His face had a battered Mike Tyson look, probably

from his early days as a pugilist. The applause came to a sudden

halt followed by open-mouthed amazement. What happened next is

hard to believe unless you were there. In a second, Alton

realised what he had walked into, smiled at the audience,

curtsied and strutted down the catwalk in short effeminate steps

with one hand on his hip. At the end of the catwalk he bowed

with one arm behind his back and retreated back through the

curtain. By then, the women and kids were laughing out loud and

applauded as if they'd witnessed a performance by a top

entertainer. They had! On another visit by Alton we had moved house to a cottage with very low ceilings. We had an old upright piano, the top of which was only about 2 feet from the ceiling. Immediately above the ceiling was the bed we slept in. I was awakened one morning by the piano beneath being played. It was Alton playing Hey Look Me Over. My mind went back to the days when he was one of my heroes in the jazz history books and on records. I shed a tear as I thought, "How many people can say that they have been awakened to this?" Over the years Alton made several trips, and was always a very welcome houseguest. On one tour he was accompanied by Barry Martyn on drums (Alton being a member of Barry's 'Legends of Jazz' band. This boosted the band no end. On one of many visits we were temporarily without trumpet, but I managed to book the superb Cuff Billett to travel up to Manchester, which again gave the band a great lift. Eventually the management changed, and Ken Pitchford took over from Tom Stagg. Ken was sometimes helped out by a lovely man from the Derby area called Ivan Merritt, who sadly died before Ken did. Wingy Manone

Of all the US visitors, the only real controversial and white one was Wingy Manone, the famous one-armed trumpet player. His arm was severed by a street car on Canal Street in New Orleans when he was an infant, so he had a dummy hand with a black glove on it. I was worried about him before I met him. I had been warned not to even think of inviting him to stay as a house guest, but to put him in a guest house, otherwise he would upset my children and insult my wife. I was also advised to keep him working without a day off, even if the fee was less than the usual. The late piano player Jon Marks brought him up from London. Jon was to stay with us and I booked Wingy into Birch Hall, a country house hotel. The proprietor was Ray Hibbertson who was a jazz fan and occasionally put on jazz events. In the flesh, Wingy certainly suited the description of his

temperament. He looked like a cross between Mr. Punch and Daniel

Quilp in Dickens' 'The Old Curiosity Shop' as illustrated by

Phizz. The first concert was at our Saturday night residency at

the Nags Head in Manchester, playing to a full house. Before we

started, Jon, Wingy and I were at the bar and Wingy told us that

the only good band left in New Orleans was the Dukes of

Dixieland because coloured musicians didn't have any feeling for

this kind of music. Jon and I glanced at each other, but neither

of us said a word. I certainly didn't want an argument before we

had played even one note. The clarinettist in the band was the

late Gabe Essien who was of mixed race, having a black African

father and white mother. He took the first solo of the evening.

At the end, nobody clapped, but that was normal behaviour at

that particular venue. Wingy frowned into the audience, grabbed

the mike, and pointing at Gabe said, "Give him a hand, he's a

nice boy!" I realised that he just liked to be controversial for

the sake of it. In other words, his bark was worse than his

bite. For those who don't live in the Manchester area I'll try to

describe Spanish. His real name was John Basnett and he was a

well-known eccentric on the jazz club circuit. He wasn't a

musician, but he was like an encyclopaedia on dates and

personnel of old Traditional jazz records and films. He tried to

live his whole life in the past and anything beyond 1950 was

described as 'crud’. For the rest of his tour I remember taking him to a club in

Nottingham, very close to Trent Bridge cricket club, and also to

Eric Clark's club at Ormsby, St. Margaret. When we arrived, Ian

Rose our drummer became ill with food poisoning from some fish

and chips that we'd stopped for on the way. Luckily Jon Marks

was still with us. He was also a good drummer so was able to

take over, although it did deprive us of his Purnell-style piano

playing. All in all, Wingy Manone's visit was a worthwhile

experience and quite educating for everyone, including the

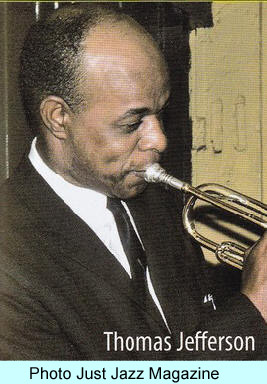

special quest himself. Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was a great trumpet player, but he was

completely bonkers.

The next day I set off with him to Boston. Lincs, to a club run

by Ivan Jessop, a fellow trombonist who had a butcher's shop in

the nearby village of Kirton. We set off in my little beetle and

as it was autumn, I put the heater on. Within a few minutes, as

the car warmed up, it was filled with this awful smell and I

realised that it was Thomas' shirt. I asked him how long he had

been wearing it and he said about six weeks! On reflection, I

think I should have told him that it was in need of a wash, but

I didn't. Another of his tales was that he was convinced he was the first cousin of Louis Armstrong, even though he was a foot taller. Apparently, Louis saw him in another American city and announced to the audience, "That's my cousin." I thought at the time that it was because he recognised a fellow New Orleanian, but I suppose it could be true.

When I drove him back to Manchester airport for his flight back

home, he was still in the same shirt, and I spent the next few

days feeling sorry for the passengers around him on that flight. In those days only a skeleton staff operated on Sundays. My journey back started about 9am on a slow train that stopped at every station on the way to Manchester. The journey took about nine hours. If that wasn't bad enough, it was a non-corridor train so had no buffet car and no toilet and I hadn't brought any food or drink with me. Somewhere along the way I jumped off to rush to a toilet at a station. I can't remember if I had permission from a guard or just took a chance. I know that it didn't do my nervous system any good. I alighted from the train at Manchester about nine hours later and headed for my car for the final half hour's drive home; I was tired, grubby, hungry and thirsty and in need of another toilet visit. My consoling thought was that my £2 fee was still safe in my wallet, ready for a visit to the bank on Monday. My next thought was: Who'd quit show business? or as the great Frank Brooker says when things aren't going as he planned, "Yep, there's no business like it."

Sam Lee Reed player Sam first came to the attention of people in Europe when he toured with a band called the Louisiana Joymakers. The front line was himself and Sammy Rimington, also on reeds. Born in Louisiana, Sam moved to New Orleans in 1926, where he played clarinet and tenor sax. He was very pleasantly eccentric, and was a pleasure to have around. He had his own strange way of talking in that at the end of each sentence he added a string of strange noises, like - Yow wow bow wow, bow yow wow. At college he met and became good friends with alto player, the great Earl Bostic. Sam arrived to us accompanied by Ken Pitchford who had taken over from Tom Stagg. Ken told us a story about driving Sam up into the mountains when he was in California. Sam saw snow for the first time and was so excited that he said he had to take some back to show his friend Purnell, who he said had also never seen snow. He scooped handfuls into the boot of his car and drove straight to Purnell's house. When Alton opened the door, Sam exclaimed; "Purnell, come and see this quickly. Yow wow yow bow wow." Of course, when the boot was opened, all that remained was a puddle of water. He stared in dismay at the scene, then pointed at the boot and mumbled, "Yow wow bow wow yow wow!" Round about this time we had a good friend staying with us for a few days. During a social evening I put on an LP of Earl Bostic, which I had recently purchased. Included on it was his hit parade single 'Flamingo'. My friend scowled at this sound, and asked me if I would put on some real New Orleans music. I pointed out that Earl Bostic was a native of New Orleans, so it was New Orleans music. My friend grumbled 'You know what I mean,' and had me put on some older style revivalist band, which he obviously enjoyed much more. By sheer coincidence, only about a month later, Sam Lee was with us to do a little tour, as was our aforementioned friend, who had asked if he could stay with us again in order To hear Sam Lee play. Because I thought that it might be of interest to Sam, I once again put on the Earl Bostic L.P. Sam's eyes instantly lit up. 'You Bow Wow' he exclaimed excitedly 'That's my friend Earl. We went to College together.' On hearing this, our other guest grabbed the record cover and handed it to me, saying, 'Say Dave, where can I get a copy of this record? There's now't as queer as folk.

Wallace Davenport

After leaving Ray Charles, Wallace returned to New Orleans in order to play what he called "Dixieland with Dignity". Tom Stagg, who organised the visit, had told me that Wallace also didn't want to be anyone's house guest, so I booked him in at a guest house only a couple of miles away. Tom arrived by car with his wife and daughter and a friend, Alan Ward. We drove out to Manchester Airport to collect Wallace from the plane, dropped him off at his B&B, then Tom and co. stayed with us. Wallace was booked at Rotherham with the Brennan Band. At Manchester with my band, and a Sunday night concert at Leeds, organised by John Wall, which I played on, although I think it was mainly the Brennan personnel. At that time, trumpet player Dave Pogson led a band called The Magnolia, which had a residency at a pub in Oldham called the Grey Horse. Jack, the landlord, was a magistrate in the town, and an alcoholic, as were most of the regulars. The pub was a real grotty old boozer with a carpet that had long since turned into compost. Another carpet had been put over the top of it and was quickly heading the same way. I took a friend in there once who was a probation officer. As soon as he entered the pub, he looked around and exclaimed; "Bloody hell! Half my case load is in here tonight." Lots of after-time drinking went on when the band finished. It was not unusual to see several policemen outside watching us walk to our cars. I think that Jack had an arrangement with them that as long as there was no trouble, he was allowed to continue plying his trade.

Wallace had accepted an invitation to Sunday dinner, so I invited him to the Grey Horse lunchtime session before we ate. He declined an invitation to sit-in with the band, so I asked him to judge an Easter bonnet competition. Here is a photo of him with these ladies, all wearing flowery hats and some with missing teeth. It being Easter, we had a request for a hymn, which I led in. On the way home Wallace said that he would like to record some hymns and spirituals, and invited me to be on the recording. Naturally I was thrilled and flattered, bearing in mind his status and history. We didn't discuss any more details, so I suppose that I just waited for the airline ticket and contract to come in the post without any further effort from me. The Grey Horse eventually became 'Mabel's Chippy' and is now another kind of restaurant. I went several times for a sit-inside meal when it was a fish and chip shop, and could see the ghosts of all the famous musicians who dropped in there. I thought that there should be a plaque on the wall, but the names would not mean anything to most people. On a visit to New Orleans about 20 years later I saw this stooped old man with a zimmer frame, slowly making his way out of a jazz joint on Bourbon Street and entering another. I asked the lady on the door of the club he'd left, if he was Wallace Davenport. When she confirmed that he was, I hurried down the street to intercept him. I re-introduced myself and expected him to say; "Dave, at last you're here. I was almost giving up on you." Instead though, he looked puzzled and eventually said; "Sorry, I vaguely remember the name of a bandleader in the north of England, but I think his name was Dave Brennan." It still hurts .

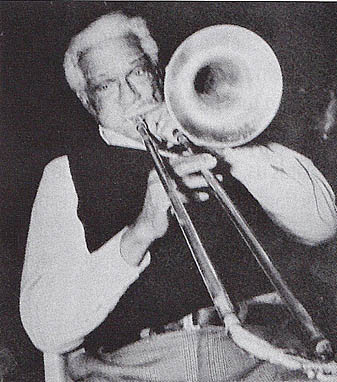

Louis Nelson Over several years, this great and very

popular trombone player was our most frequent visitor. I'd got

to know him on my 1971 visit to New Orleans, so that helped, and

over the years I began to look upon him as a true friend.

When he died, the headline in the 'New Orleans Music' magazine said 'Farewell Mister Nelson' I can explain the origins of 'Mister' Louis always introduced himself simply as Nelson, and informed me once that only his real friends called him Louis. (I was eventually promoted to this status.) Anyway, during our residency at The Crown in Manchester, one of our weekly regulars was a man named Alan who had an art gallery in the city. One night I was asking him how it was doing. He told me that sales were fairly steady, but the top sellers were the prints of Mister Lowry. I asked him about his constant use of 'Mister' when referring to L. S. Lowry. He informed me that it was simply a sign of respect. I related the story to Johnson, our late bass player, and from then on we used the name Mister Nelson whenever his name came up. Ken Pitchford told a few people about our referral, and eventually it began to be used amongst musicians in Europe. If anyone has a different version then it will be like the real Heidi House or Robert Burns' birthplace. There is only one. One Sunday lunchtime I offered to take him to the Grey Horse pub in Oldham to hear The Magnolia. He immediately put his dentures in and picked up his trombone. I feigned surprise and said, "Oh, are you taking your instrument?" He replied, "Of course, I am. I know what you boys are like. When I arrive I'll be expected to play." It was true, and to everybody's delight he obliged. The truth was that he wouldn't miss a chance to have a blow, anywhere, anytime. I've been at impromptu parties with him and as soon as a trombone was produced, if he wasn't invited to play he would ask the owner if he could borrow it, even if its owner had only played one tune. One of the most memorable incidents happened in a small village near to Sleaford on a quiet Sunday afternoon. We were on our way to play with the local band at Boston Jazz Club. Ivan Jessop, the bandleader, was a fellow trombonist and had a butcher's shop in the small village of Kirton, Lincs, where we were going to stay. Although I had been before, I was unsure of where to turn off for our destination. The village was deserted apart from an elderly couple walking towards us. I pulled up and wound the window down to ask directions to Kirton. They began explaining to me, then suddenly spotted this brown hand in the passenger seat and began stooping lower to obtain a look at the rest of him. This seemed to irritate Nelson and he frowned at them, at the same time making coughing, growling sounds to show his annoyance. Eventually the couple were bent double, talking to me whilst never taking their eyes off Louis. As we drove off, he said, "What the hell was wrong with those folks?" I explained to him that he was probably the first non-white person that they had ever set eyes on. This didn't change his mood, however, and we travelled in silence for a while. I found my turn off and we went along a single track road. The only relief from the total flatness in all directions was the occasional pile of rotting turnips. This seemed to be the last straw for Louis, and he suddenly exploded, "God dammit Dave, where the hell are you taking me? Nobody lives around here." He only slipped back into his normal calm self when we reached our destination and could relax with welcoming people and refreshments.

One day while staying with us, Louis asked me if I would drive him into Ashton-Under-Lyne as he needed some paste for cleaning his dentures. I needed to drop something off at my parents' house, and as they lived not far out of the town, I drove there when we had done his errand. I asked him if he would like to pop in and meet them? He replied, "Damn right I would!" They still lived in the same mill worker's terraced two-up two-down that I was born in. They welcomed him in, and my mum instantly produced tea and biscuits which were gratefully accepted. As we drove away, Nelson's first words were, 'Them's nice people Dave. Them's proper people.' I must say at this stage that although I knew Louis Nelson to be very articulate (his parents being a doctor and a school teacher) he occasionally enjoyed speaking in the vernacular, maybe from mixing much of the time with less educated musicians than himself. The following Saturday night, as we arrived for Nelson's concert with us in Manchester, our drummer, the late Ian Rose couldn't wait to relate the following story: Ian was very friendly with my younger brother Mike, who also is no longer with us. He was a frequent visitor to my Mum and Dad's house, where Mike still lived. He had called to pick up my brother during the week, as Mike didn't drive. My mother told him I had been round the previous day with my friend from America and that he was very nice and accepted a cup of tea and a biscuit. Ian couldn't get over the fact that people were travelling from miles around to watch a performance by the famous trombonist from New Orleans, whereas all that mattered to my mum was that he was my friend, was very nice, and had a cup of tea with them. On later visits his lady friend/partner, Sue, accompanied him on his tours, and stayed with us a couple of times. At the end of every visit, before we drove to the airport, Louis always emptied his pockets of all sterling coins for my children to share out. Soon after one of his trips he sent over pencils for all of them, engraved with 'Louis Nelson Trombonist' on one side, and each of their names on another side. He had become like an uncle to them. Talk about nice and proper people! Kid Sheik

When I formed my own band, Sheik was our band

guest and house guest several times over the years. He had a

lovely disposition, and was never anything but happy looking in

any situation. He never displayed any flashy technique in his

playing but did what the trumpet in a band is supposed to do,

play the melody. lf anyone needs proof of his creativity

however, just listen to the counter melody he plays on Yees,

Sir, That's My Baby on the Olympia Brass Band recordings. His

tone is also unmistakeable. The nickname given him by his fellow

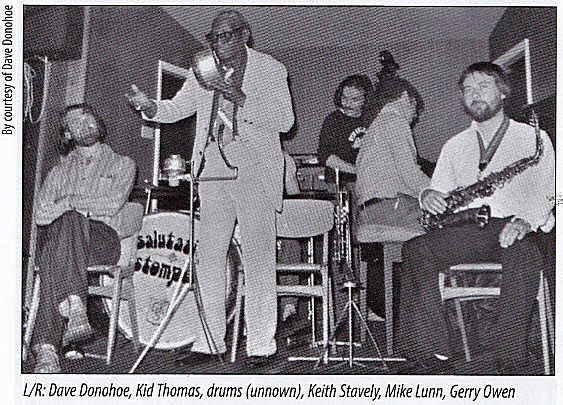

N. 0. musicians was, 'The great Diz' Kid Thomas In the world of jazz music I have always thought, along with others, that all trumpeters, whatever style, had varying degrees of Louis Armstrong influence in their playing. The only exception to this being Thomas Valentine. He is unique and prehistoric. He is like the marmite test of Traditional jazz. I don't suppose that anyone would argue that the Three Tenors weren't better singers than Tom Waites or Kris Kristofferson, but it comes down to who you derive most pleasure from listening to. One night I arrived too late for a seat at Preservation Hall and had to sneak in by the back entrance and stand amongst a group of American tourists, all listening to the Kid Thomas band. During the set the band played Memories. Kid Thomas put a mute in and stood up to take a solo, playing the melody so quietly that you could hear a pin drop. The man in front of me turned to his companion and whispered "Jeez, and I thought Harry James was good." I once worked in an ad agency in which the chief copy writer was Frank Dixon. Apart from being a doppelganger of the late broadcaster Gilbert Harding, he presented a weekly jazz programme on Radio Manchester, so I was quite pleased to work in the same open-plan department as Frank. I also learned that he was very knowledgeable on classical music. One day I missed my bus to work through listening to a Bach Brandenberg Concerto on the radio and decided that I would like to buy a recording of it. I knew that there was more than one, and so I asked Frank if he could advise me on which one it was. He told me that there were six in all and then went on to hum all of them in sequence. When he finished, about an hour later, he began questioning me about my interest in jazz.

The first I learned of a visit to the North of England by Kid Thomas Valentine came through a phone call from my friend Keith Moore in Preston. He had been asked to put a band around Thomas by Mike Casimir who had organised five jobs. Keith asked me to be in the line-up of the first band at Leyland, Lancs., along with Johnson, the bass player in my band. Richard Milward was driving Thomas up from London, but I was asked, I think by Keith, if we could take him as a house guest for one night as he was booked to play up in South Shields on a Sunday with Brian Carrick's band. I couldn't have been more thrilled at the prospect. I didn't see the event, but apparently Keith and the Preston boys put Kid Thomas in the Leyland Carnival the next day, it being Saturday. He was put in an open top car, and as he slowly passed the vast crowds that lined both sides of the road, he smiled at them and gave them the royal wave as if the whole event was arranged in his honour. Naturally, and to their loss, the crowd didn't know him from Adam. When I brought him home to stay after the concert in Leyland, my wife made us a cheese and biscuit snack for supper. I decided to put some background music on. I chose an LP of country songs with things like Your Cheating Heart and other Hank Williams' and Jim Reeves' favourites, all done by a little known group, a bit like the Cliff Adams Singers of 'Sing Something Simple' fame. The first one was I Love You So Much It Hurts, a song that I have on an LP by Thomas. After less than a minute he said, "I like that music. That's really pretty music. I ain't heard music like that in a long time." I told him that I was pleased with his approval, and sat back smugly complimenting myself on my good judgement. A minute later he suddenly asked, "Do you like Johnny Cash?" At the time I was indifferent to Johnny Cash. (I quite like him now, but not all his material.) He asked it in a way that made me think that Johnny had a serious fan. So wishing to keep him in his happy mood, I replied, "Yes, I quite like him. Do you?" "Shit No!" he shouted, and threw his plate of cheese and crackers up in the air. I thought it best to close the subject.

In contrast to these little spats of cantankerous behaviour, I discovered the next day that he did have a boyish sense of fun. Along with chickens, geese and fantail pigeons at that time, we had a nanny goat called Susie. Every time Thomas set eyes on her, if I was there he would say, "I want to eat that goat." Then he would turn to my wife, with a smile, and wink at her. Our arrival at the club in South Shields for the Sunday evening concert was another memorable experience on my travels with musicians, and also showed the kind and thoughtful side of the trumpet player, who seemed to enjoy being seen as controversial. Trumpet player Colin Dawson, who as far as I know is having a successful career playing jazz in Germany where he has lived for many years now, was born and raised in South Shields and went to the local music college. He had no particular music style to aim at until he discovered Kid Thomas. A similar story to Mike Owen and Kid Ory. I had told Thomas in advance about a young fan who would be there waiting for him. (Colin would be about fifteen at the time.) As we walked up the steps to enter the hotel foyer, a crowd was there to greet us, and naturally at the front of the queue was young Colin with his mum and dad. As we passed, within touching distance, Colin's eyes and mouth were wide open in disbelief as though he was being granted the Beatific vision. He simply uttered "Gosh!" He had just been given proof that Kid Thomas Valentine really did exist. Half way through the evening, Thomas, without any prompting from anyone, pointed down at Colin who was sitting at his feet, and said, "Come on boy, come and sit up here and play at the side of me." I knew at that moment whatever his idiosyncrasies were, his heart was in the right place. Milton Batiste The invitation to put on this unique

character and trumpet player came from the late Mick Burns who

at the time was in London and in the 'Rue Conte' band with

trumpeter Mike Peters in the 1990s. Most readers will know now

that Batiste was the deputy leader of Harold Dejan's Olympia

Brass Band of James Bond film fame, Imitation New Orleans bands

weren't laughed at in the street as much after 'Live and Let

Die' came out. Trumpet player Alvin Alcorn is the assassin who

stabs the man who asks, whose funeral it is as the band

approaches. My first encounter with The Olympia was in 1971 when the charter flight was met at New Orleans airport by the band. A few days later I was allowed to join them on a funeral. Batiste ('Bat' as all his fellow musicians called him) was always kind as regards allowing people to join them as long as they asked first. When we were in Ascona, Switzerland, they would always allow me to go out on the street with them. On one of the visits 'Bati' came out with my Hi-Life Brass Band and taught us a lesson in dynamics. We were joined by Richard the grand marshal who was Milton's stepson. He always called Milton 'Dad', as he was only two years old when Milton married his mother. Having agreed with Mick to arrange a concert up north, I booked a local brass band club which had a good concert room and a licensed bar. At the time another band in Manchester were booked to play at a jazz club only a few miles away from the venue that I had booked for the next night. When they heard of Milton's forthcoming visit, the leader arranged for this club to take him as a guest with them. This was obviously upsetting because it might have an effect on our audience and ticket sales, plus the other band were on a guaranteed fee from the jazz club, and I had agreed to pay the guest's return train fare from London on top of his fee. I spoke with the other band leader (whom I'd known for thirty years) on the telephone and explained the situation, and asked if he would agree to share the rail fare with us as a gesture. He didn't readily agree, but said that he would consider it. On the day after their concert we met for a handover of Milton, and the man handed me a sealed envelope just before driving away. Over a pub lunch I opened the envelope, assuming that it was a cash contribution towards the train fare. It wasn't. It was a letter containing words to the effect that any arrangements over money I had made was of no concern to anyone else, and vice versa, and he had no intention of contributing anything. Milton saw the look on my face as I read it, and asked if anything was wrong. I told him the whole story and showed him the letter. He also looked disgusted and said, "Goddamn, I sat at the table watching him write that letter'. In the 1960s the person I am discussing was in the Ged Hone Band at the same time I was. He took leave of absence and went off on an adventure to the Far or Middle East. A few weeks later Ged received a letter from him to say that he was in jail for some law breaking offence. He said he had to pay a sum of money in order to be freed and deported. I can't remember the details, just that he desperately needed the money. None of us had any disposable income at the time, but decided that as a mate we ought to help him. We found the money between us and he eventually arrived back. The moral of the story is, if you help someone, don't assume that they will return the favour if it needed at some later date. I like to think that people with this attitude are in the minority. Back to the Batiste situation: I had to think of ways of drawing people in to our concert. I decided to create variety by doing part brass band, part smaller jazz band and part symposium by having Milton sit on stage and answer questions from the audience, if he would agree. Luckily he did agree. I put all this on the publicity as well as emphasising the Olympia's involvement in the Bond film. As hoped, we had a sell-out, and the evening went as planned. Everyone was happy.

For winter wear I adapted and outfitted the band in firemen's dress jackets made of wool. Batiste saw these at the Cork Jazz Festival in October and asked if I could find one for him, and post it to him, which I did. A couple of years later I was introduced to his wife as the man who sent him the warm jacket. Everybody eventually is remembered for something. I discovered the firemen's jackets in an old mill that used to be an Army and Navy surplus store but now could sell you anything from a gas mantel to a ship's anchor, or even the occasional Sherman Tank. Writing this has reminded me of an incident in my childhood which I'd like to relate. When these surplus stores opened after the war I bought an American helmet and a parachute for about a shilling each. The helmet covered my eyes, ears and nose, and the parachute was for dropping food parcels, so it was only about four foot diameter. I thought that was the normal size. I told several local girls that if they came to the back of our terrace at a certain time, they could watch me jump off our lavatory roof and float to earth in my parachute. The lavatory was a separate building at the end of the yard. When my audience arrived, I climbed onto the roof via the dustbin and a wall, and waited for the breeze. The circle of girls stood impatiently looking up at me and muttered things like," Well? Go on then." At the first hint of breeze, I launched myself into space like a true war hero. The parachute remained completely unopened as I hurtled down like a stone. I was wearing thin canvas pumps. My first point of contact with terra-firma was one big toe and a broken brick from the recently demolished communal air raid shelter. I still wore short pants, and my bare knee collided with the other half of the brick, ripping my skin off. As I lay on the grass clutching my injured knee, I tried to look as though I wasn't in as much pain as I really was. The girls rolled their eyes to heaven in disgust and simply strolled away. The next day, I crossed out 'Flying' on my list of things to consider if wishing to get into the world of entertainment. BACK TO MUSIC During the concert there were lots of questions from the audience. Someone asked 'Bat' what motivated him to do what he did, musically? Without hesitation he replied "Money': Back home after the show my youngest son and I stayed up for a late drink and an unwind with Milton. After a while my son followed me into the kitchen to tell me that Milton had said that he wished he had a bit of weed to smoke. I reminded him that he and his pals were the ones who dabbled in that, and that I didn't have any. I only touched it when it was somebody else's. My son produced some grass that he had grown in a pot at work. This pleased 'Bat' very much. After a while I needed to empty my bladder. As it was about 1.30am and we weren't overlooked by neighbours I decided to use the garden. Soon after, Batiste stood up and said," I need to pop up to your loo Dave". Our only bathroom was upstairs, so I told him that we were well away from the road and passers-by, and he could use the garden, as I had done, if he wished. Now at the time he was dressed in red trousers and a red shirt, and his beard was turning white. He thought for only a second before coming out with one of the best spontaneous replies I have ever heard. "Thanks, but I don't think so". You can imagine the phone call from the neighbour, "Hello police? I know that it's only October, but Santa's arrived early. He turned black. He smoking a big reefer, and he's pissing all over the rhubarb'. The last time I saw the full Olympia band was at Porthmadog in Wales. They were playing for a funeral of a man who had made his fortune in America, and following a visit to the Crescent City had put in his will that he wanted a real New Orleans funeral in his home town. It was great to see 'Bat' instructing the police chiefs where to position the horse-drawn hearse so as not to frighten the animals. I don't know the details, but not long after that he had one leg amputated, followed by the other one, an extremely sad end for a man who contributed so much to the world of marching bands. The members of that great band are all gone now along with the other legends. I remember Jon Marks in Celerina, when he knew he had not long to live saying to me, "Weren't we lucky in knowing all those old men? And didn't we learn a lot from them?" A great quote to finish these stories. Thanks Jon. After several years of these tours by U.S. musicians, age and health began to take its toll, and they became less frequent. Barry Martyn played and stayed with us several times, at least twice with his sons, Emile and Ben, who went swimming in the local reservoir with my children. We also had the pleasure of playing a successful concert with trumpet player Theodore (Teddy) Riley in Peterborough. Teddy had an exciting attacking style. He worked and recorded with many Rhythm & Blues and brass bands. Sadly the brass band records were never issued. In 1971 Riley played on the cornet used by Louis Armstrong in his youth for the New Orleans ceremonies marking Armstrong's death. Over the next few years the band had many other visiting British guests. These included Ken Colyer, the lovely Pat Halcox, Keith Smith, clarinettist Cy Laurie, and Monty Sunshine who always referred to me as Sam Donoghue. Following an American tour back in 1977 organised by Sammy Rimington and Butch Thompson, Butch came over and stayed for a week, as did trumpeter Geoff Bull from Australia. Terry Dash brought the trombonist Freddy Lonzo from New Orleans to do a concert with us. I haven't grouped Fred in with the Legends as he is of a much younger generation, but he a great player. Much of his style is influenced by the great Waldron 'Frog Joseph. Terry also arranged a week's tour with us for Swedish clarinettist, Orange Kellin (still living in New Orleans) which proved enjoyable for all. ADDENDUM: Just after I finished writing this last story I learned of the sad death of John Pashley, a good character, and a professional Yorkshireman. My mind instantly went to the lakefront in Ascona where the Olympia were performing on the street. I had just arrived and so ran excitedly towards the sound. They were in a circle surrounded by a crowd, and the first person I recognised was John. It was a very hot summer's day and he stood out in a thick Harris tweed jacket. I stood at his side and said, "Hi Pash'; He did not return the greeting, but turned and simply exclaimed, "Ain't that the truth man!" I would like to mention that, to my knowledge, not one of the American musicians featured in this series ever touched alcohol. I do know that some were reformed alcoholics, but I didn't think it was my right to pry into their personal lives. It was obviously important to them to preserve their high standard of professionalism and to be able to keep touring. -

Dave Donohoe

|

When

the concert, which was well received, was over, Wingy decided

that he didn't want to go straight back to his hotel but on to

somewhere for a drink and a chat, which pleasantly surprised me.

Being a Saturday night, we found a late night drinking pub in

Ashton-u-Lyne on the way home. He kept us entertained with

stories of Al Capone and his mob in Chicago, and how musicians

were treated very well by them. He told us about threatening to

stop the band playing, and remonstrating with some sailors one

night because they were shouting racist comments about the

clarinettist Edmond Hall who was in his band that night, adding

to my theory about him wanting to be controversial. I asked him

what he thought of Louis Armstrong, and he replied; "Well of

course you had to listen to him because he was so good."

When

the concert, which was well received, was over, Wingy decided

that he didn't want to go straight back to his hotel but on to

somewhere for a drink and a chat, which pleasantly surprised me.

Being a Saturday night, we found a late night drinking pub in

Ashton-u-Lyne on the way home. He kept us entertained with

stories of Al Capone and his mob in Chicago, and how musicians

were treated very well by them. He told us about threatening to

stop the band playing, and remonstrating with some sailors one

night because they were shouting racist comments about the

clarinettist Edmond Hall who was in his band that night, adding

to my theory about him wanting to be controversial. I asked him

what he thought of Louis Armstrong, and he replied; "Well of

course you had to listen to him because he was so good." Without my knowledge he had been booked into a B&B at Eccles,

about six miles from Manchester City Centre, and I lived about

ten miles in the opposite direction. I dropped him off and said

I would collect him later for the concert. When I collected him

I was surprised to see that he was still wearing the same thick

woolly shirt that he had arrived in. I commented on this and he

explained that he had brought a tuxedo and bow tie with him, but

when he played in all the jazz clubs on the continent, everyone

was dressed very casually, so from then on he'd just played in

the only casual shirt he'd packed. Thomas was received very well

even though he talked as much as he played.

Without my knowledge he had been booked into a B&B at Eccles,

about six miles from Manchester City Centre, and I lived about

ten miles in the opposite direction. I dropped him off and said

I would collect him later for the concert. When I collected him

I was surprised to see that he was still wearing the same thick

woolly shirt that he had arrived in. I commented on this and he

explained that he had brought a tuxedo and bow tie with him, but

when he played in all the jazz clubs on the continent, everyone

was dressed very casually, so from then on he'd just played in

the only casual shirt he'd packed. Thomas was received very well

even though he talked as much as he played. One day I received a phone call from the late Ken Matthews, the

bass player in Newton Abbot. He'd been told that I had had

dealings with Jefferson and they were putting him on, but needed

a trombone player. When I said that it was a heck of a long way

for me to travel for just one concert, he agreed and went on to

say that all the money would be going to the guest player and

the best he could do for me was to pay my train fare, put me up

at his home and offer me a fee of £2. I replied that I couldn't

possibly refuse an offer like that, and agreed to do it. John Shillito was to be the other trumpet player, so that made it two

people I already knew. On the journey down I kept hoping that

Thomas had changed his shirt. He had, and was dressed in a smart

blazer and tie (see photo). I think that the clarinettist was

Keith Box. The night proved to be very enjoyable, unlike the

return train journey the next day.

One day I received a phone call from the late Ken Matthews, the

bass player in Newton Abbot. He'd been told that I had had

dealings with Jefferson and they were putting him on, but needed

a trombone player. When I said that it was a heck of a long way

for me to travel for just one concert, he agreed and went on to

say that all the money would be going to the guest player and

the best he could do for me was to pay my train fare, put me up

at his home and offer me a fee of £2. I replied that I couldn't

possibly refuse an offer like that, and agreed to do it. John Shillito was to be the other trumpet player, so that made it two

people I already knew. On the journey down I kept hoping that

Thomas had changed his shirt. He had, and was dressed in a smart

blazer and tie (see photo). I think that the clarinettist was

Keith Box. The night proved to be very enjoyable, unlike the

return train journey the next day.

Sometimes when we were on the road, Louis

would call out a song, and if I knew it, ask me to hum it to him

at a slow to medium tempo, then tell him when I stop to breathe.

When I stopped to take in more air, he told me that I should

keep humming for the whole sixteen bars, and then breathe. I

eventually learnt the technique by making sure my lungs were

completely empty before I took the first breath. A simple

lesson, but one that I have found to be extremely helpful.

Sometimes when we were on the road, Louis

would call out a song, and if I knew it, ask me to hum it to him

at a slow to medium tempo, then tell him when I stop to breathe.

When I stopped to take in more air, he told me that I should

keep humming for the whole sixteen bars, and then breathe. I

eventually learnt the technique by making sure my lungs were

completely empty before I took the first breath. A simple

lesson, but one that I have found to be extremely helpful.

I enclose a photo from the Daily Express 1963 showing Sheik

between me and Eric at the long-gone Central Station which is

now an exhibition and conference hall. Keith Moore and the late

Ron Pratt are the clarinettists. Ron is the one who looks like

Peter Lorre. The press called Sheik' The grand old man of jazz'

He was fifty six.

I enclose a photo from the Daily Express 1963 showing Sheik

between me and Eric at the long-gone Central Station which is

now an exhibition and conference hall. Keith Moore and the late

Ron Pratt are the clarinettists. Ron is the one who looks like

Peter Lorre. The press called Sheik' The grand old man of jazz'

He was fifty six. It was 1964 and the Atlantic recordings of the Thomas band had

just become available in Britain. I told Frank that those were

the LPs that I was currently listening to and enjoying. "Ah

Yes", said Frank, "I'm familiar with Kid Thomas. In fact when I

go round lecturing on jazz I always take a Kid Thomas record

along with me. "Do you?", said I. Thinking that I had found a

real soulmate at last. "Yes;' replied Frank, "I use it as an

example of how a trumpet should never be played." I skulked

back to my desk and kept out of his way after that. My

admiration of him had diminished by several notches. I still

bought the Brandenbergs though.

It was 1964 and the Atlantic recordings of the Thomas band had

just become available in Britain. I told Frank that those were

the LPs that I was currently listening to and enjoying. "Ah

Yes", said Frank, "I'm familiar with Kid Thomas. In fact when I

go round lecturing on jazz I always take a Kid Thomas record

along with me. "Do you?", said I. Thinking that I had found a

real soulmate at last. "Yes;' replied Frank, "I use it as an

example of how a trumpet should never be played." I skulked

back to my desk and kept out of his way after that. My

admiration of him had diminished by several notches. I still

bought the Brandenbergs though. Before retiring to bed, we had to stand on the landing for a

couple of hours whilst Thomas instructed us on how to renovate

and almost re-build our home. He used to be a house painter and

repairer before deciding to become a living legend.

Before retiring to bed, we had to stand on the landing for a

couple of hours whilst Thomas instructed us on how to renovate

and almost re-build our home. He used to be a house painter and

repairer before deciding to become a living legend.